On 31st May 2016 the New York Times published the op-ed below (under a title that is unfortunate and not my choice). (For the NYT site, click here.) The version below is the original and contained graphs and data that could not be fitted in the printed version. (You can also download a pdf of the full article here.)

Athens — After last summer, when the clash between Greece’s recently elected Syriza government and the insolvent state’s creditors ended, the world’s media moved on. The brief rebellion against the austerity measures imposed on Greece was snuffed out in July 2015 when Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras folded.

Greece’s disappearance from the financial headlines since then has been seen as a sign that its economy has stabilized. Sadly, it has not.

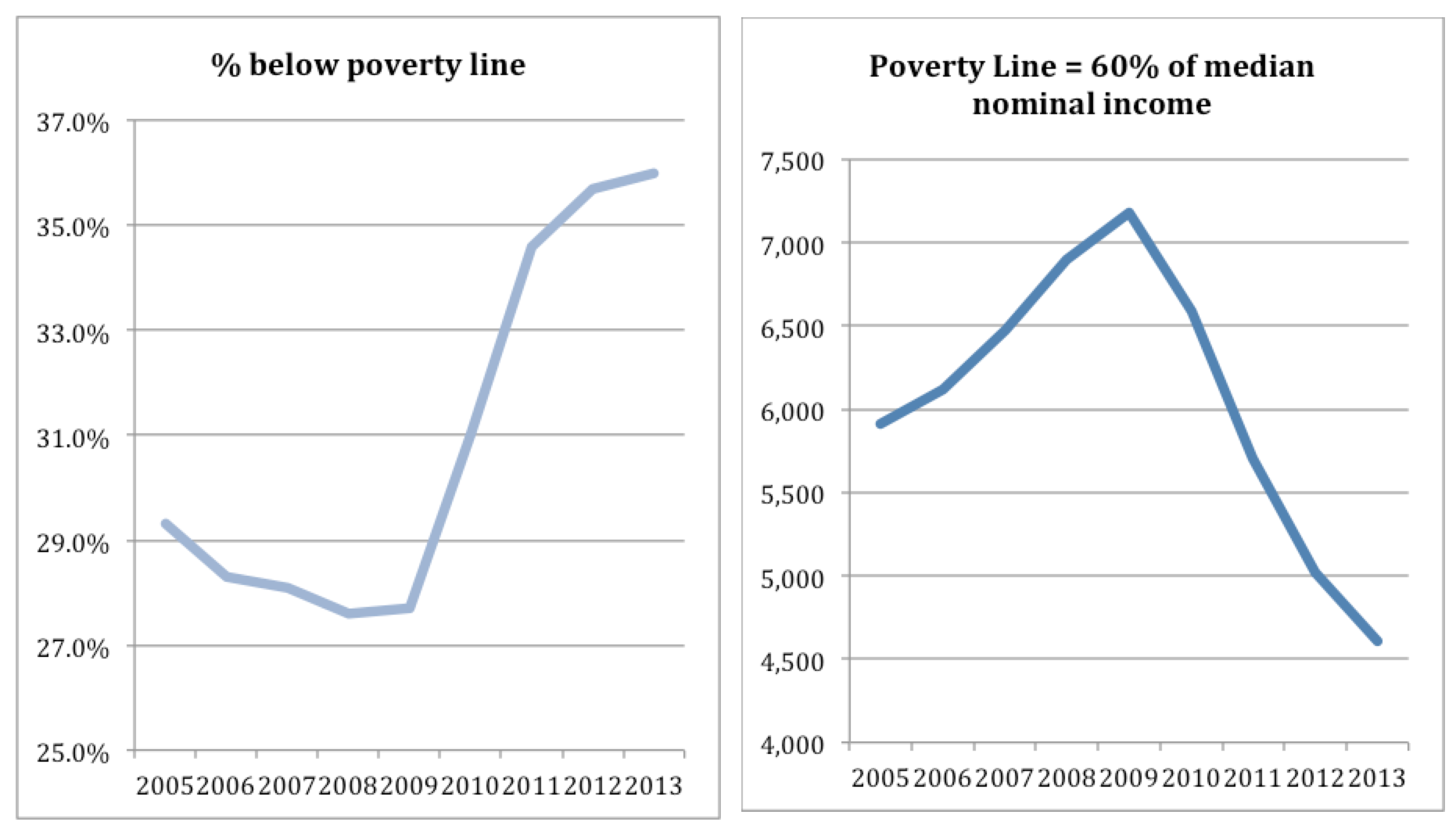

Lest we forget, Greece had already endured years of austerity. By 2013, more than a third of Greeks were living below the poverty line. By 2014, government wages and pensions had been cut 12 times in four years.

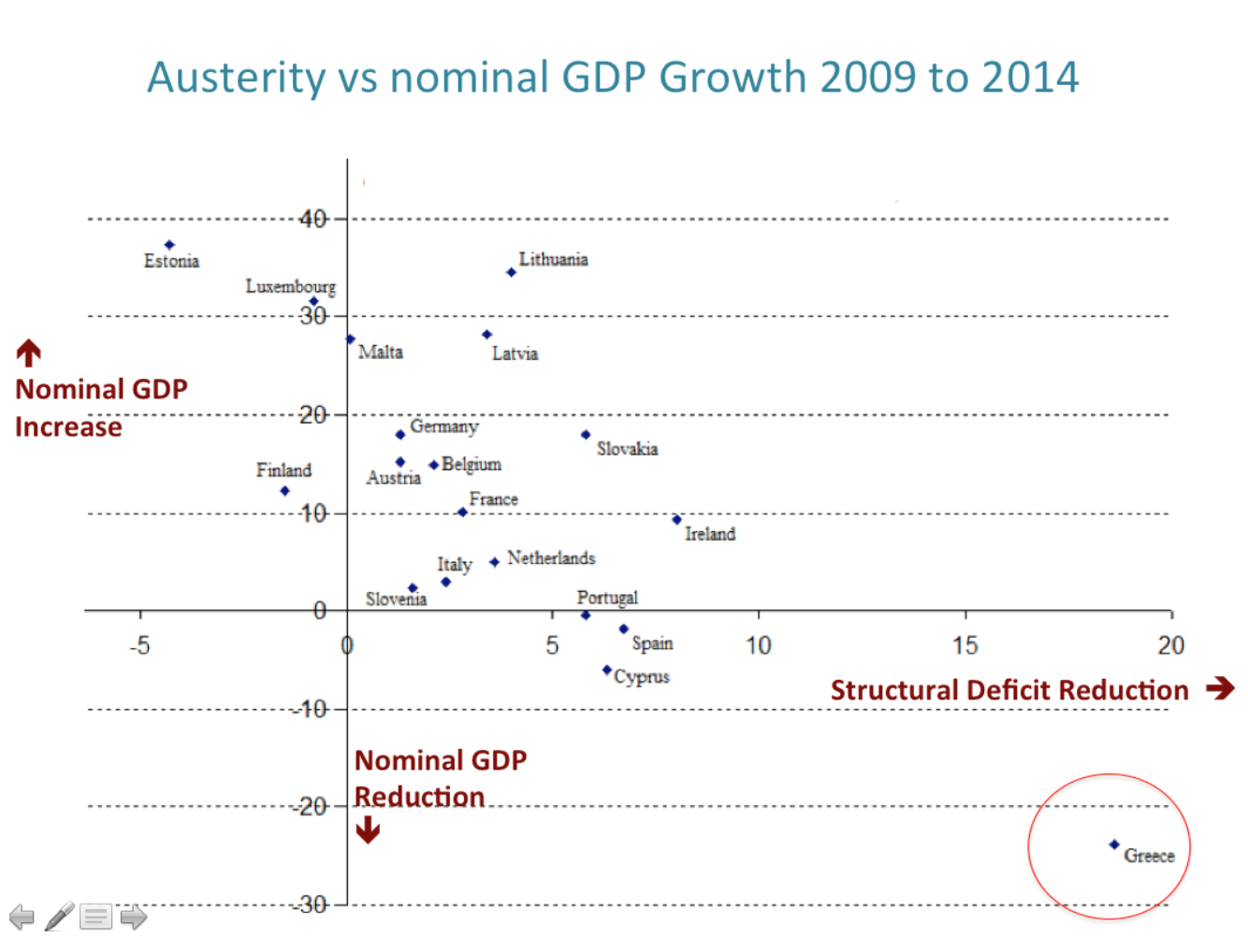

In comparative terms, Greece had absorbed austerity measures almost nine times the magnitude of those imposed in Italy and more than three times Portugal’s. The result? Between 2009 and 2014, Italy’s economy grew by a paltry 2 percent and Portugal’s contracted by 1 percent; in the same period, Greece’s national income dwindled by a catastrophic 26.6 percent — about the same as for America in the depths of the Great Depression (see Figure 1). The result was a humanitarian disaster only a latter-day John Steinbeck could adequately describe (Figure 2) for poverty data.

FIGURE 1 – Increase/Reduction in the structural deficit in percent of GDP terms versus nominal GDP growth/contraction. (Nb. A government’s budget deficit is computed as the difference between government expenditure and tax revenues as a percentage of national income. The structural deficit is computed in the same manner except that national income is estimated as the average of the nation’s income in the good and the bad years of the cycle.)

FIGURE 2 – The left hand side graph shows the percentage of the Greek population whose income falls below the official poverty line. The right hand side graph depicts the fluctuations of the official poverty line (which is conventionally drawn to equal 60 percent of median income). The combination of these two graphs reveals the extent of the humanitarian crisis: Between 2009 and 2013 (Nb. data for 2014 and 2015 is not in yet), the poverty line has fallen (along with median income) from €7,178 to €4,608. Despite this momentous drop, the percentage of the population that fell below that free-falling poverty line shot up from 27.7 percent to 36 percent. Moreover, this distressing trend has been continuing unabated for another three years (2014 to 2016), as the official data is bound to confirm.

Against this background, Greek voters elected my party, Syriza, in January 2015 to negotiate an end to self-defeating austerity in exchange for serious reforms. With the state now living within its means (i.e. new government expenditure was slightly lower than tax revenues), I strove, as the country’s new finance minister, to convince our European and institutional lenders that their interest and ours would best be served by reducing tax rates and avoiding further cuts to already much reduced pensions. As a compromise, I even promised a “deficit brake” — automatic tax hikes that would kick in if government revenues did not pick up within an agreed period.

Our sensible debt restructuring ideas and my deficit brake proposal fell on deaf ears, and I resigned. Greece’s creditors insisted instead on even higher sales taxes, as well as new cuts in pensions and wages. The Greek government’s capitulation to the creditors even involved a preposterous obligation that all Greek companies should pay, immediately and in full, their estimated tax for the next year. The cruel screw of austerity turned again.

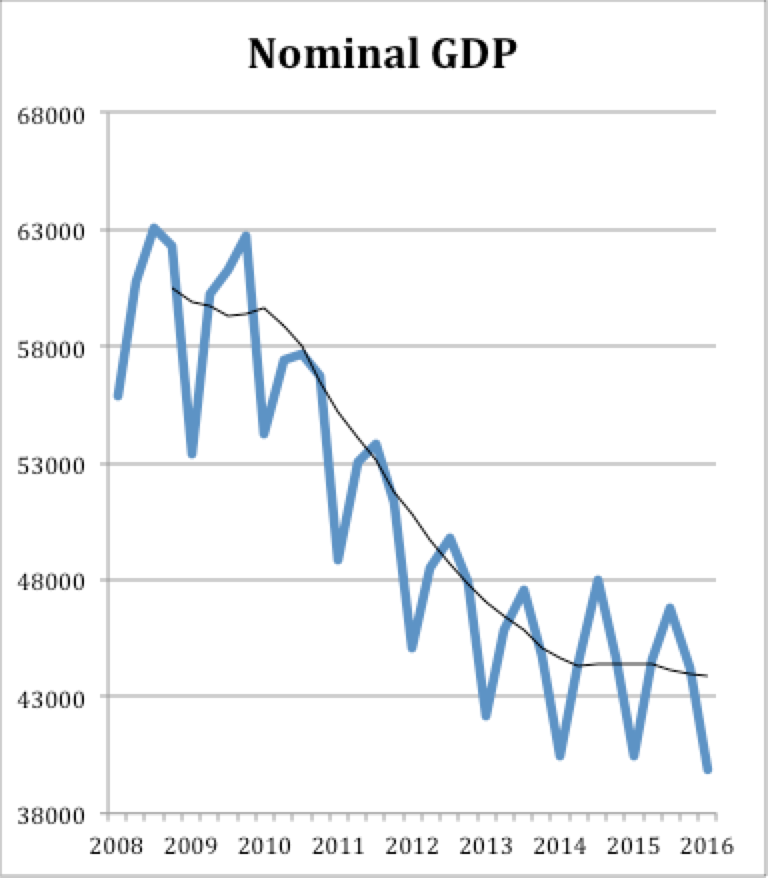

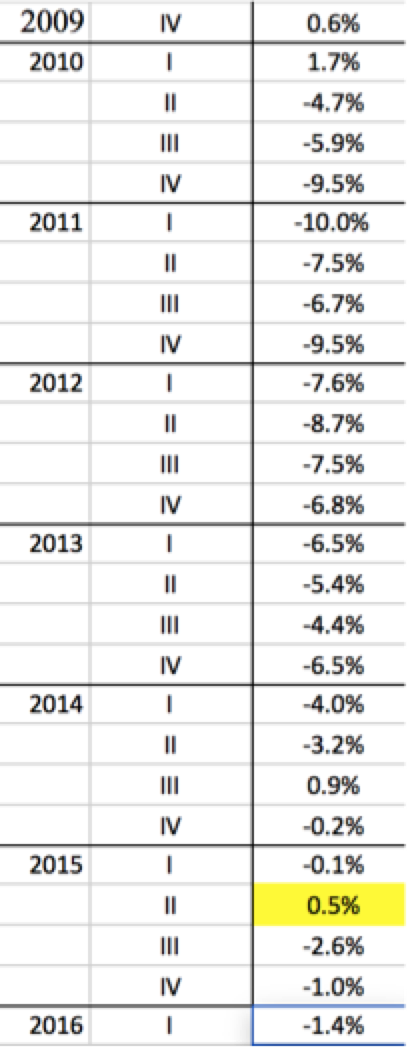

Once the new measures were implemented, incomes in Greece, which had picked up slightly while we put austerity on hold, began to fall again. (Figure 3 demonstrates that, indeed, the second quarter of 2015, when austerity was on hold, was the only quarter since 2008 of positive nominal income growth.)

FIGURE 3 – On the right, seasonally unadjusted quarterly (annualized) nominal GDP growth (Nb. Note that 2015Q2 was the only quarter of positive nominal income change. On the left, the downward path of nominal GDP in absolute numbers (GDP measured in market prices).

But the bank closures that were forced by Greece’s creditors to make our government yield, and the new austerity that followed, revived the recession (see, again, Figure 3). This increased the number of nonperforming loans on banks’ balance sheets — up to an astounding 45 percent of all loans — with the effect of denying credit to potentially profitable export-oriented firms. One in every two Greek families has no member earning a wage, while the cuts in public spending mean that for the past two years less than 10 percent of the jobless receive any unemployment benefit.

Behind the grim numbers, an ugly reality looms, one that gets uglier by the day. Small businesses have been crushed by punitive taxes, and a wave of home foreclosures is on the horizon. Greece’s hospitals are running out of basic necessities, while our universities cannot even afford to provide toilet paper in their restrooms. In Athens, these days, only the soup kitchens can be said to be flourishing.

Amid this endless suffering, have any lessons been learned? It seems not.

Greece’s economic misery seemed set to provoke a new standoff recently — except that, this time, it was between the International Monetary Fund and the European Union’s Brussels-Berlin nexus. Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany is reluctant to confess to the Bundestag that Greece’s bailout loans were always unsustainable. To maintain the fantasy that they will be repaid as planned under the terms of last year’s deal, Berlin has insisted on setting a ludicrous target for Greece’s budget surplus. (That target is 3.5 percent of gross domestic product every year from 2018 to 2029; that amount is roughly equivalent, as a percentage of G.D.P., to America’s military budget — but in Greece’s case, purely to service its foreign debt.)

The German condition, that the European Commission is echoing, amounts to imposing permanently escalating austerity on Greece. The I.M.F. protested, correctly, that there is no level of austerity that can achieve this target. Indeed, judging by its spokesman’s comments as well as conversations between members of its staff published by Wikileaks, the I.M.F. had embraced the exact surplus target that I was proposing last year as well as most of the debt restructuring ideas I had put forward together with Jeff Sachs and Larry Summers.

In past weeks, there were many indications that the fund was ready to insist on this mixture of debt relief and a lower surplus target, and so less austerity. Unfortunately, last Tuesday’s meeting of the so-called Eurogroup — an informal body of eurozone finance ministers together with officials from the European Central Bank and the I.M.F. — dashed these hopes. With the I.M.F.’s managing director, Christine Lagarde, notably absent, her stand-in capitulated to the Brussels-Berlin axis, postponing any prospect of debt relief until talks a year or two hence.

Earlier this month, Athens had obediently introduced a fresh round of tax hikes and pension cuts — the sales tax in Greece now stands at 24 percent. The I.M.F.’s view is that these measures will fail to attain the impossible surplus target. The fund is right about that, but the new solution it has condoned is as bizarre as it is counterproductive.

Instead of reducing the surplus target, the I.M.F.’s representative at the Eurogroup meeting, Mr. Poul Thomsen, consented to the extraordinary decision to retrieve from the trash basket of last year’s negotiations the deficit brake that I had proposed in exchange for an end to austerity. The idea is that if the 3.5 percent surplus target is missed — and it will be — then new tax increases and spending cuts will kick in automatically. So, the very instrument that I had proposed as a substitute for austerity will now become its supplement. The mechanism will merely accelerate Greece’s downward spiral of austerity and recession.

Reason demands an end to this loop of doom. All Greece needs is a realistic restructuring of its debt, a primary surplus target of no more than 1.5 percent of national income and continued reforms that target oligopolies in economic sectors like supermarkets and the energy sector, as well as inefficiency and corruption in public administration.

Instead, the odd principle of imposing the greatest austerity for Europe’s most depressed economy lives on, spreading new misery through Greece and needlessly holding back recovery in Europe’s monetary union.