For The Telegraph site, click here. Otherwise…

‘Europe is too important to be left to its clueless rulers’

So, I say to Yanis Varoufakis, you were an obscure university lecturer, with a sideline in writing comment pieces about economics, who had also devised and plotted virtual currencies for computer games, but your only experience of political office was almost 40 years ago as secretary of the Black Students Alliance at the University of Essex (even though you’re white) – how exactly did you end up for five months as one of the pivotal figures in the biggest economic crisis to engulf Europe since the Second World War?

‘Well…’ Varoufakis gives a slight smile. ‘Accidentally…’ Varoufakis –‘The emerging rock star of Europe’s anti-austerity uprising’ (Daily Telegraph), ‘The bad boy of European politics’ (almost every newspaper in Europe) – is sitting in the fourth-floor apartment in a middle-class neighbourhood of Athens where he lives with his wife, Danae Stratou, an artist well known in Greece. Sunshine pours through the balcony doors on to the blond wood floors, tasteful, modern furniture, the interesting art on the walls.

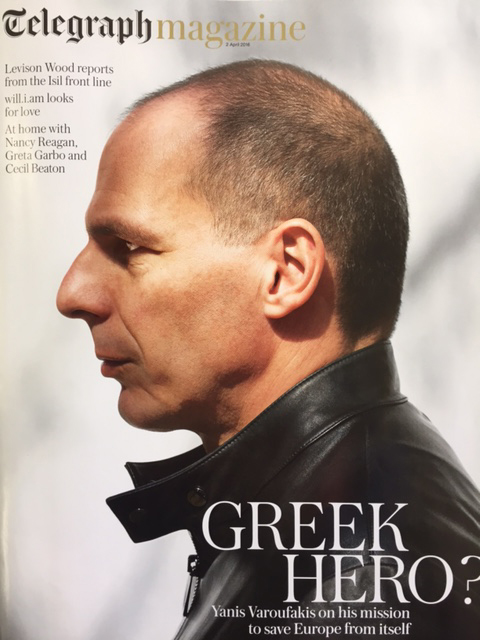

Varoufakis, 55, has the hawkish profile of a battered ancient coin. He shakes hands firmly and fixes me with an unwavering gaze. He is dressed in a stylish shirt and trousers. He looks lean and fit – more like an ex-footballer than a retired politician.

It is eight months since Varoufakis resigned as Greece’s finance minister, in the wake of the historic referendum when the Greek people voted to reject the demands of the country’s creditors, the so-called ‘troika’ of the European Union, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. It was the result that Varoufakis and the Greek prime minster Alexis Tsipras had been campaigning for. But within 24 hours Tsipras had performed a volte-face, accepting the troika’s terms. Varoufakis resigned.

A politician without office, Varoufakis now spends his time writing, giving speeches and campaigning to reform Europe from the grass roots up. In February he launched Diem25, a pan-European umbrella group, aiming to pull together left-wing parties, protest movements and ‘rebel regions’ from across the continent, with the object, as he puts it, to ‘shake Europe – gently, compassionately, but firmly’, and bring ‘democracy back to EU decision making.’

He has published a new book, And the Weak Suffer What They Must? – a detailed historical analysis of the origins of Europe’s financial crisis. Its basic thesis is that the eurozone is not the route to shared prosperity it was intended to be but ‘a pyramid scheme of debt with countries such as Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain at its bottom’. Its conclusion, put bluntly, is that Europe ‘is too important to be left to its clueless rulers’, and that the eurozone must be ‘fully recalibrated’ if Europe is to avoid a ‘postmodern’ repetition of the 1930s, with financial chaos, the rise of fascism, and the spectre of conflict.

He has recently returned from Abu Dhabi, talking to business leaders at the Global Financial Markets Forum. For every 15 lectures he gives for free, he gets paid for one, he says, ‘but that’s good enough’. And the self-described ‘erratic Marxist’ is a popular draw among bankers and financial institutions. ‘I say to them exactly what I say to a left-wing audience,’ he says. ‘For some reason bankers like my analysis of the euro and global crisis. They’ve had enough of people telling them what they think they want to hear, because that hasn’t worked very well for them in the last seven or eight years. The fact they want me to talk to them is a sign of how deep this crisis is.’

Varoufakis is a man with a broad hinterland. A tour of his bookshelves reveals everything from Greek philosophy to Marx, from Isaac Asimov (‘I’m a science-fiction freak’), to Zionism in the Age of the Dictators (‘that’s a great book!’) and the complete works of Iris Murdoch (‘The Sea, the Sea is my favourite. I’m crazy about Iris Murdoch’). He speaks beautifully, in the deep, eloquent cadences of the European high intellectual.

He is a particularly felicitous phrasemaker. Talking of the ‘irrational’ policies of the eurozone, he likens them to the belief of people in the Middle Ages ‘that the plague was caused by sinful living and could be exorcised through self-flagellation’. In the course of a 14-minute TED talk, ‘Capitalism Will Eat Democracy’, that he gave last December, he managed to shoehorn in both Aristotle’s formulation for democracy (‘the constitution in which the free and the poor, being in the majority, control government’) and the legend of Oedipus, to illustrate a point about low aggregate demand.

Listening to Varoufakis’s analysis of a politics that embraces Marx, Keynes and Hayek, his interlocutor confessed to being ‘confused’. ‘If you’re not confused,’ Varoufakis said with a laugh, ‘you are not thinking, OK?’ ‘That’s a very, very Greek philosopher kind of thing to say.’ ‘That was Einstein, actually,’ Varoufakis replied.

His father, George, was born in Cairo, emigrating to Greece in the 1940s and arriving in the midst of the country’s civil war. As a student leader, he was told to sign a denunciation of communism. When he refused, on the grounds that ‘I am not a Buddhist, but I would never sign a denunciation of Buddhism’, he was sentenced to five years’ ‘political reeducation’ in a prison camp on the island of Makronisos.

He went on to become chairman of Greece’s biggest steel producer, Halyvourgiki. Varoufakis was six when the military junta came to power in 1967. At the age of 14 he was arrested and spent a night in jail after distributing leaflets on behalf of the socialist party. Reasoning that his son would be safer out of the country, his father decided that following secondary education he should move to Britain, and in 1978 he enrolled in a course at the University of Essex, studying mathematical economics.

He signed up to every left-wing cause on offer – solidarity with Chile and the PLO, Troops Out of Ireland (he resisted joining the Socialist Workers Party: ‘I could never stand Trotskyists’) – and became a spokesman for the Black Students Alliance, on the grounds that ‘black is not a question of colour – it is a social issue’. He went on to lecture at Essex, and spent a further year lecturing at Cambridge, before leaving in 1988 for Australia and a post at the University of Sydney.

It was there he met his first wife, a Greek-Australian historian. The couple returned to Greece, but separated in 2005 shortly after the birth of a daughter, Xenia, whose mother took her back to Australia. The first few years of separation from Xenia were ‘awful’, Varoufakis says. ‘I raised her partly through Skype. She had a screen on her cot as a two-year-old and I used to read her stories and watch her fall asleep.’ He laughs. ‘I’m a great advertisement for Skype.’ They now see each other four or five times a year.

It was shortly after that separation that he met his present wife. Stratou is the daughter of a wealthy Greek industrialist – her grandfather founded one of Greece’s largest textile companies – and a sculptor mother. In the 1980s she studied sculpture at Central Saint Martins in London, overlapping with Jarvis Cocker, the singer with Pulp, leading to much speculation when Varoufakis came into the public eye that Stratou was the girl ‘who came from Greece’ and ‘studied sculpture’ in Cocker’s song Common People. (Cocker is vague on the subject.)

For much of the Noughties, Varoufakis was an obscure academic, lecturing and writing abstract pieces on mathematical economics, in specialist journals ‘which only 10 or 15 people in the world were reading’. But as the world stumbled towards recession in 2008 he began to acquire a reputation as a Cassandra, warning that Greece was heading for bankruptcy and arguing against the first bail-out in 2010.

Alexis Tsipras had become leader of the left-wing Syriza party in 2009, and began to turn increasingly to Varoufakis for advice. ‘Syriza was a very small party then – four per cent of the vote,’ Varoufakis says. ‘Their line was the equivalent of Brexit; I warned him against that and changed his mind.’ In 2012 Varoufakis moved to America, but two years later, when it looked as if Syriza might win the election on a promise to renegotiate Greece’s debt and significantly curtail austerity measures, Tsipras approached him to ask if he would return to Greece and join his cabinet.

Lord Lamont, the former Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer, first met Varoufakis in 2012 at a conference in Melbourne, debating Europe. ‘We were on opposite sides,’ Lamont remembers, ‘but actually had the same point of view. We both agreed the euro was a pretty bonkers idea, but he was saying Greece couldn’t get out of it whereas I was saying it should be dismantled altogether.’ The two became good friends. In 2015, on the eve of the election, Varoufakis emailed Lamont. ‘He said, you may find this as surprising as I do, but if opinion polls are right, tomorrow I’ll be a politician. Even worse I may become the minister for finance.’

‘I never intended to go into politics, ever,’ Varoufakis now says. ‘You can ask my wife. I always said, this is not for me; I wanted to remain a public intellectual and that’s it. But there is a moral duty that one has. Once you’ve been criticising and saying we shouldn’t be doing this, we should be doing that, and somebody says, “OK come and do it”, what do you say then?’ Varoufakis now looks back at his time in office with a mixture of rancour, amusement and self-justification, as the most exhilarating, stressful, exhausting, tumultuous – ‘all of these things’ – five months of his life.

‘The first couple of months were pure delight, because Alexis and I were united. We were on the side of the angels, and I felt energised that we were doing this together. But when I felt the troika had pushed a wedge between us, this delight turned into horror. And I stayed as long as I did only out of duty to the prime minister, because I felt that even though he was making compromises that would lead to surrender, there would come a moment when he would be so humiliated that he would turn to me and seek solutions.’ He shrugs. ‘It didn’t happen.’

Greece’s fate, he suggests, was determined by an interlocking network of political agendas that had nothing to do with saving the economy: the long-standing enmity between Germany and France; and the fact that the Spanish, Irish, Portuguese and Baltic countries had all imposed their own programmes of austerity that would have made it political suicide to side with Greece.

‘Take the Spanish government. If the negotiation I was conducting was successful, how would Rajoy [Mariano Rajoy, the Spanish prime minister] be able to answer his opposition in parliament, and the people on the street, when they asked, why didn’t you do something similar to Greece? They had a vested interest in making sure we didn’t get anywhere in the negotiations.’

Then there was Wolfgang Schäuble, the German finance minister – whom Varoufakis, borrowing from Tacitus, had accused of reducing Europe to a desert, and calling it peace. ‘For him Greece is collateral damage,’ Varoufakis says. ‘He doesn’t care even about Portugal or Italy. He cares about France, and the troika process here in Greece is a way of keeping Paris under his thumb.’

Varoufakis says Schäuble’s position was made crystal clear at an early meeting, when he pointed out to the German finance minister that the Syriza government had been elected on a mandate to challenge the whole philosophy of austerity, and that some form of compromise would benefit everybody. ‘I said the previous programme had failed. So let’s find a way of recalibrating to stop Greece being a drag on everybody else. I thought this would go down well.

And Schäuble astounded me. He put his hand up and said, “Elections cannot be allowed to change the economic programme for Greece.” And my response was, this is a great gift to the Communist Party of China, who believe exactly the same thing.’ He gives a mirthless laugh. Varoufakis himself was to prove a great gift to the media – the pugnacious leather-jacket-wearing, motorbike-riding, shaven-headed intellectual, taking on the grey bankers and bureaucrats of Brussels.

He appeared on the steps of 11 Downing Street with George Osborne dressed in an open-necked shirt! He flew economy! He had a way of presenting the impenetrable complexities of euro finances in highly quotable soundbites: the troika was subjecting Greece to ‘fiscal waterboarding’, while the euro was akin to the Hotel California in the Eagles song, a place where ‘you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave’.

Le Monde christened him ‘the rock economist’. The German magazine Stern lauded his ‘classical masculinity’. The Portuguese socialist MP Isabel Moreira lost it completely, swooning excitedly on Facebook, ‘The Greek Minister is so damn sexy.’ Varoufakis waves all this aside with an air of weary impatience. He may look – as was constantly mentioned – like Bruce Willis, but he is clearly at his happiest when discussing what reforms he would make to the European Stability Mechanism.

It would be fair to say that his adversaries in the troika were less enraptured. A man of adamantine self-belief, he was accused of being arrogant, intransigent, cantankerous and worse. ‘I don’t think anybody in the EU had ever dealt with a finance minister like this, who instead of rolling over said we’ll fight,’ one close observer says. ‘He’s a street fighter; and he loves it. They couldn’t believe it.’

When in April 2015 at a Eurogroup meeting in Riga an unnamed source told a reporter that Varoufakis was considered a time-waster, a gambler and an amateur, he replied in a tweet quoting Franklin D Roosevelt, ‘They are unanimous in their hate for me; and I welcome their hatred.’

When I ask whether it’s true that at one particularly heated meeting he headbutted Jeroen Dijsselbloem, head of the Eurogroup, Varoufakis gives a pained sigh. ‘No, no, no. Dijsselbloem and I never had a good relationship, but it was always cordial and civilised. Only once were voices raised a little bit.’ He pauses. ‘Imperceptibly, I would say. ‘Really, it’s astonishing what has been said about what happened behind closed doors. I’m a contrarian – but in the sense that I like a good argument. I get bored when everybody agrees. But I never had a bad moment with anyone at a personal level.

All these reports that in the Eurogroup meeting I was called names, a time-waster, a gambler – that never happened. There was intentional distortion that was extremely damaging and very hurtful to me. And they all took that back when I said, “And by the way, I’ve recorded all the meetings and I’m going to release the tapes…’’

So, politics is a dirty business? ‘I never expected it to be anything else. But I did have the expectation that when after a long process of convergence with someone who is a significant player, you reach an agreement, and you shake hands, that that means something. And then the next day, or the next week, they pretended it had not happened. Then you know that this is dirtier than you thought it was. I have to tell you I did not expect that.’

He says that following his resignation many people in Greece approached him about founding a new party to lead the opposition against the Tsipras government. ‘I said no, because by that time we’d had a small window of opportunity to change Greece’s situation and we missed it. Alexis and I failed together. So starting a political party, to put forward a new programme with promises I knew I could not fulfil, even if I were elected prime minister – what’s the point of that?’

It is one of the peculiarities of the argument over Europe that it goes beyond the traditional political dichotomy of left and right. While he acknowledges having spent his formative years ‘joining every demonstration I could find’ against Margaret Thatcher, Varoufakis writes admiringly in his new book of her final speech in Parliament in 1990, when she rejected the idea of linking sterling to the European Monetary System and a European Central Bank ‘accountable to no one, least of all to national parliaments’.

‘It was perhaps the first and last time the prime minister of a major European nation hit the nail on the head regarding the nature of Europe’s monetary union,’ he writes. ‘I do miss Thatcher,’ he muses at one point in our conversation, almost fondly. ‘She and Keith Joseph had such a clear way of expressing their views.’ He is no friend of right-wing parties. But he says he has ‘a great deal of resistance’ to left-wing parties, too; ‘they are very authoritarian’.

Despite serving in the Syriza government, he was never a party member. And his friendships cross the political spectrum, from the Conservative – Norman Lamont – to the egregious – Julian Assange. ‘I like him a lot,’ Lamont says of Varoufakis. ‘He’s extremely clever, and very unorthodox. And for a left-wing Greek he’s surprisingly in love with England.’ Lamont laughs. ‘He is not a straight up and down leftist, let alone a Marxist. He recognises the importance of markets and the private sector. He’s not in favour of excessive debt. He recognises the need for responsibility. I think he’s been unfairly caricatured in many ways.

‘And I believe he was absolutely right in his stand against the troika. The degree of austerity that was being heaped upon the Greeks became completely counterproductive. The reality is that Greece is bankrupt and Greece’s debt will never be repaid, and he recognised that right at the beginning.’

Greece, Varoufakis says, is now in a worse state than it has ever been. Rises in VAT and corporation tax have imperilled small businesses and caused a stampede of big business across the border to Bulgaria, where corporation tax is 10 per cent (in Greece it is 29 per cent). Investment is plummeting.

He now describes the eurozone as being in ‘a 1930s moment’, sliding inexorably towards disintegration. ‘The question is, are we past the point of no return?’ He leans forward in his chair. ‘I very much fear that it can’t be saved, but at the same time I’ll be damned if I’ll idly sit here watching it happen.’

Happily, he believes he has a plan – what he calls ‘The Modest Proposal for Resolving the Euro Crisis’, a four-point programme drawn up with the help of his friend the American economist James Galbraith and Stuart Holland, the former Labour MP and a professor at Sussex University, and modelled on the New Deal that pulled America out of recession in the 1930s.

These include a restructuring of European banking institutions to encourage investment and revitalise (or kill off) ‘zombie’ banks, reduce public debt and develop green technologies, and the introduction of a European Food Stamp, ‘because the levels of poverty in Greece, Portugal, parts of Ireland – parts of Germany – are increasing and fuelling ultra-nationalism, racism and xenophobia to a very large extent.

‘All it would take is one press conference where Mario Draghi [president of the European Central Bank], Angela Merkel, Jean-Claude Juncker [the President of the European Commission] and the head of the European Stability Mechanism put forward this programme for saving the eurozone; that would be enough. It would only take half an hour and the shock of optimism that would emanate from that press conference… But will they do it?’ He sighs. ‘The answer is no.’

Varoufakis’s view that Europe is broken, undemocratic, its economic policies dominated by petty-minded, unaccountable bureaucrats and careerists, might seem to lend encouragement to supporters of Brexit. But on the contrary. As a person who ‘lives and breathes Europe’, he believes that Britain must remain in the European Union and try to reform it.

The argument that Britain can leave and stay in the single market is fallacious, he says. ‘To have a single market you need three things: common industry standards; common labour market rules; and common environmental protection standards. And to have these you need common legislation; you need a common judiciary that will enforce these laws, and an executive for implementing them.

In other words, you need a pooled sovereignty. And if you get out of the European Union while staying in the single market, effectively you are transferring the three branches of power to an alien entity – Brussels. So I think in the end you will end up with less sovereignty, not more, because you won’t have the power of veto.

‘There is a major mistake being made by both sides of the debate in Britain. They are presuming that the EU is a constant, a given – but it’s not. It used to be a work in progress; now it’s disintegrating, and Brexit would hasten that disintegration. If Britain comes out, at some point a major fault line will develop down the Rhine and across the Alps.

Germany is going to simply create a new Deutschmark zone with the Netherlands, Poland, the Czechs, Slovakia and the Baltics. Maybe Belgium will be split up. In that environment, Britain is going to suffer, even if it’s out of the European Union. There would be a black hole in Europe that Britain will be sucked into – without gaining sovereignty.’

On the day we met, 18 refugees were drowning off the Turkish coast in an attempt to reach Greece, while tens of thousands more were massing at the border between Greece and Macedonia. Varoufakis is a strong proponent of open borders. Angela Merkel, he says, may lead a government that has ‘effectively strangled’ Greece, but her action last year in opening Germany’s door to migrants ‘is a great source of joy for me to be able to say I am proud of what she did. I believe we have a moral obligation to refugees to let them in.’ He sighs. ‘What is happening to Europe, and our integrity as Europeans?’

Of course there is a difference, he goes on, between refugees and migrants. ‘And there should be different policies. But I have to tell you that as a human being and as a European citizen, I am very keen to be alive to the fact that there are many ways you can be terrorised. You can be terrorised by a bullet, or you may be terrorised by the sight of a child starving. And having two different policies that say if you’ve been terrorised by a bullet you can come in, but if your child is starving you stay out, is something that doesn’t agree with me morally.

‘In the 1930s, when a lot of Jews fled continental Europe, you didn’t do a cost-benefit analysis to say can we afford to let them in or not? You just open the doors and then you work it out. And usually those refugees are the ones who are most productive and make the greatest input. The 20,000 refugees at the border between Macedonia and Greece, you could put them somewhere near Glasgow and nobody would notice – and the food would get better.’ He gives a faint smile. ‘One needs to make such exaggerations in order to make a reasonable point.’