In reply to the “Critique on the Modest Proposal” by Andreas Koutras[1]

If you think that the Euro-17 Treaty change agreed yesterday will help overcome the eurozone’s Crisis, read no further. If, however, you think that the solution lies not in Treaty changes, but requires other means, including an active role to be played by the ECB, do read on.

More than a year ago Stuart Holland and myself put forward the Modest Proposal for Overcoming the Euro Crisis. It has never been more pertinent than now. Most commentators, globally, agree on two things:

- This Crisis will not melt away unless the ECB adopts an active role, and

- The ECB will never be allowed, primarily by Germany, to intervene by printing money.

If both (1) and (2) are correct (as I am sure they are), what can be done? Our Modest Proposal answers simply: The ECB should step in not by printing money but by borrowing on behalf of the member-states. Pure and simple. Moreover, we claim, if the ECB borrows by issuing its own bonds (ECB-bonds hereafter), it will become possible to use this new instrument not only to reduce the eurozone’s overall debt burden but also to finance (together with the European Investment Bank) a New Deal for Europe.

But is it that simple? Our Modest Proposal, whenever and wherever we presented it, met with the immediate response that Central Banks do not issue bonds for a reason; that there will be no taxpayer to back them up (thus raising questions about the interest rates of these ECB-bonds); that our proposal conflates fiscal with monetary policy; that it constitutes a backdoor policy for having the ECB print the money needed by the member-states; that such a move would jeopardise the ECB’s independence etc.

We have been answering (see here for an example) these rejoinders for more than a year (with considerable success, I might add, judging by the fact that our Modest Proposal has been adopted by important organisations, such as the ECTU, and approved by assorted bankers, many former Heads of State, financiers etc.) Nevertheless, with the eurozone in such an advanced stage of disintegration, and our leaders committed to searching for solutions in the fairyland of Treaty amendments, it is important to re-examine our Modest Proposal and, in particular, the idea that (1) and (2) above can be combined by having the ECB borrow rather than print; by turning the ECB not to a lender-of-last-resort but to a debt-converter-of-last resort.

Koutras’ Critique (readers preferring to read the long text below on pdf please click A Reply to the Critique of the Modest Proposal by A. Koutras)

The impetus for revisiting various criticisms of our Modest Proposal came in the form of a recently published critique. Indeed, Andreas Koutras paid our Modest Proposal the complement of studying it and writing a piece in which he identifies what he thinks are serious flaws. For this I wish to thank him. Goodness knows Europe desperately needs open minds (and hearts) so as to, at long last, have a decent debate on the true nature of the Crisis, with a view to fashioning rational responses to it.

Koutras’ paper (click here for the pdf version and here for the web version) begins by noting, quite correctly, that the Modest Proposal consists of three policies but concentrates its analysis on Policy 1, the idea of ECB-bonds for the purposes of converting a large part of the eurozone’s sovereign debt. Quite clearly the author thinks that this is the bone of contention. Though I shall argue that ignoring the other two policies (especially Policy 3) causes a degree of confusion, I shall nevertheless go along with Koutras and engage with his assessment of Policy 1.

Koutras’ paper is structured as follows:

- A summary of Policy 1 (our Debt-Conversion Plan, i.e. Policy 1, according to which the ECB takes upon itself the task of servicing the eurozone’s Maastricht Compliant Debt, while simultaneously opening debit accounts for the member-states whose debt is being serviced)

- A piece on the use of Special Purpose Vehicles by banks prior to 2008 (which was, indeed, central to the mass financial destruction wrought by the financial sector itself)

- An interpretation of the ECB’s role in effecting this Debt Conversion in the context of the history of Special Purpose Vehicles

- A series of potential flaws of our Policy 1 in the context of the preceding analysis under the following headings:

- i. Overdraft Facility not allowed by Article 104

- ii. e-Bonds fail to sell?

- iii. ECB’s Independence is in peril if Credit guarantees are given

- iv. Countries take the losses (taxpayers)?

- v. Pretend it is a Liquidity and not Solvency crisi

- vi. e-Bonds are not Plain and Boring Bonds

- vii. Monetary Policy reversal

- vii Fiscal Policy-Democratic Deficit

Below I address each of these headings in turn before summing up my rejoinder to this critique.

Koutras’ summary of Policy 1 is fair and accurate. (Readers not familiar with our Policy 1 are requested to do so now – see here.) So is the historical account of the calamitous role of SPVs that brought upon us the spectre of a financial Armageddon in the Fall of 2008. Where I begin to part ways with Koutras is in the way he interprets our Policy 1 through the prism of the SPV ‘experience’. To put it simply, Koutras draws a parallel between the role we envisage for the ECB and the use of SPVs by Wall Street banks. This parallel is, I think, both unhelpful and inaccurate.

To begin with, SPVs were created, as Koutras admirably explains, in order to hide debt and to shift it from a more creditable (the bank) to a less creditable pseudo-stand-alone vehicle (the SPV). Our policy suggestion does precisely the opposite. First, the operation we are proposing is bathed in light and its success relies not in the slightest in hiding anything. Secondly, it shifts debt servicing from entities that are suffering from low creditworthiness (member-states) to one (the ECB) that is credit-worthier. In this sense, the SPV metaphor is precisely wrong. Moreover, we have gone to great lengths to clarify that the proposed tranche transfer is done on the balance sheet of the ECB itself, and not some offshoot of it (an ACME-ECB outfit, as Koutras named it for argument’s sake). Summing up:

The SPV metaphor is precisely wrong (Rejoinder I, addressing point 3 above)

“The problem with shepherds is that they see sheep everywhere”, Ibn Khaldoun once wrote. And the problem with those who cut their teeth in the financial sector is that they see SPVs, CDOs etc. whenever a re-financing schedule or operation is mentioned. I understand that. For instance, when the Europeans wanted to create a bailout fund in May 2010 (in the wake of Greek Bailout Mk1), they told their blue eyed backroom boys and girls: “We need to find a way of raising money from the strong eurozone countries to fund the ones that may follow Greece into the abyss. But we do not want to allow for one cent of common debt. How do we do this?” The answer these chaps and lasses gave was commensurate to that which they knew: Create an SPV, call it EFSF, and make it raise finance from the not-yet-fallen member-states by issuing CDO-like bonds.

At that time we put together our Modest Proposal (the Mk1 or 1.0 version) in order to propose precisely the opposite: No SPV and homogeneous bonds that look nothing like CDOS – i.e. bonds that do not consist of different slices, each with a different interest and default rate corresponding to a different eurozone member-state. To ensure this we specified that bonds are issued by the ECB itself, on the model of EIB (European Investment Bank) bonds that are issued not through some SPV but by the EIB itself.

No overdraft facilities involved (Rejoinder II, addressing point 4i above)

Koutras understands our Debt-Conversion idea well but interprets, or phrases, it in a manner that I wish to take issue with. It is, of course, true that the very idea of a Debt Conversion operation is to utilise the better creditworthiness of some party (in this case the ECB’s) in order to offer other parties (the eurozone’s member-states) interest-relief. When a creditworthy parent negotiates a low-interest rate loan by which to repay a (less creditworthy) child’s existing high-interest loan on condition that the child meets the monthly repayments, it is correct to say that the parent shifts risk from the bank to herself (and this is why the interest rate charged is reduced). But to describe this operation as the parent “selling protection” to the bank is to introduce into the equation a transaction that is simply not there. Similarly, according to our Policy 1 the ECB simply sells plain and boring bonds (in the sense that there is nothing complicated or CDO-like about them). No protection, no CDOs, not a whiff of SPVs are involved. (Of course, whether buyers will want to buy these bonds is another matter, which I discuss below.)

In the same section of his paper, Koutras quotes from Article 104, with a view to arguing that our Modest Proposal violates it:

Overdraft facilities or any other type of credit facility with the ECB or with the central banks of the Member states (hereinafter referred to as .‘national central banks.’) in favour of Community institutions or bodies, central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of Member States shall be prohibited, as shall the purchase directly from them by the ECB or national central banks of debt instruments.

Notice the keywords here regarding that which is categorically prohibited:

(a) overdraft facilities (in favour of Community institutions or bodies)

(b) credit facility (in favour of Community institutions or bodies)

(c) direct purchase of… debt instruments.

Notice too that Policy 1 of the Modest Proposal requires none of the above. Indeed, it was designed in order to preclude all of these. Let’s look at them one by one beginning backwards: We argue explicitly against the idea of ECB purchases of member-state bonds, in full accordance with (c). We also suggest nowhere the creation of either credit or overdraft facilities on behalf of member-states or other community institutions – in strict adherence to (a) and (b). In contrast, what we are suggesting is that the ECB opens debit accounts into which the eurozone member-states will be paying (as opposed to withdrawing) money. This is precisely the opposite of facilities from which member-states draw credit of one sort or another.

To sum up, Policy 1 of the Modest Proposal neither suggests that the ECB “sells protection” to bond buyers nor canvasses any form of debt purchase, bond buyback or overdraft facility for member-states. In this sense, the Modest Proposal is fully in accordance with Article 104. Koutras’ point, however, is that our scheme introduces a potential overdraft facility through the backdoor. Let us examine this claim which comes in the form of a legitimate question posed by Koutras:

“So what happens if… the government bonds start underperforming or even the sovereign stops servicing them? Does the … ECB have an unlimited liquidity commitment with the Eurozone countries? The hidden assumption of the MP is that since it is a central bank, it has its own! In the event that the sovereign cannot make any payments the … ECB would make up the shortfall for it. This would be done by printing new money or perhaps by the sovereign pawning some assets with the ECB (giving collateral). What I have just described is called an overdraft facility. If the sovereign is not able to fulfil its financial commitments the ECB offers a credit facility or an overdraft facility until the country in question recovers.

For starters, it is inaccurate to imply (via a question) that the ECB will have “an unlimited liquidity commitment” since this Debt Conversion applies only to the Maastricht Compliant part of the member-state’s debt, which is strictly finite. But let’s bypass this and move to the genuinely interesting and tantalising point; namely, that if a member-state defaults toward the ECB then the ECB will have, effectively, to extend credit to it courtesy of having to meet the repayments to ECB-bondholders itself. Clearly, in this case, we have a potential violation of Article 104 in our hands. Nevertheless, it is a violation that can be easily preventable. How? Simply by affording (as the Modest Proposal argues) the debit accounts of the ECB superseniority status. In short, by having all member-states participating in the Debt Conversion operation sign an agreement with the ECB, well in advance, that binds them to placing the servicing of these debit accounts over and above all of their other obligations. That way, even if one of the member-states, needs to restructure its overall sovereign debt, its debit account with the ECB will not be affected – unless we have massive default and the other member-states do not step in.

In any case, if public finance is the high art of the possible, it is essential to compare our Modest Proposal not to some airy-fairy, wishful-thinking-imbued, version of the eurozone but to the really-existing eurozone. As we are exchanging these ideas, the ECB is already printing money to buy at least €200 billion worth of stressed bonds on the secondary markets. [The claim that these purchases were ‘sterilised’, and therefore that no money was ‘printed’ for the purpose of buying these bonds, does not withstand seriously scrutiny.] Additionally, it holds another much larger swathe of government bonds in the form of collateral from (effectively) insolvent banks. The more the Crisis progresses unchecked the greater the volume of stressed bonds (which will more likely than not need to be haircut) inside the ECB’s reluctant bosom and the more money it will be printing in the context of a battle against markets it knows it will lose (just like it lost in the summer of 2010 the battle of preventing Portugal and Ireland from going under). To put the point not too finely, if our Debt Conversion proposal violates Article 104, the present reality violates it to the power of n, where n is an increasing function of time.

Will ECB-bonds sell? (Rejoinder III addressing point 4ii above)

Like hot cakes they will! Let me explain this conviction:

Koutras draws parallels with the ECB’s problematic sterilisation operations and the ‘distressed’ EFSF bond issues. I claim that these cases, though instructive, are not relevant to our proposal. Indeed, I have been arguing since May 2010 that the EFSF bonds are toxic and that soon no one would want to touch them. Moreover, ever since the ECB started buying Irish and Portuguese bonds (back in the summer of 2010) while, supposedly, sterilising these bond purchases, I was screaming from the rooftops that such sterilisation is simply not credible since, as Koutras rightly says, the insolvent banks can hardly participate credibly in this sterilisation operation (see It’s the banks stupid). But this is all irrelevant to the question at hand: Will investors buy our ECB-bonds at low, low interest rates, as I claim? Let me explain why I think they will (and why they tell me they will!).

First, (unlike the EFSF bonds) ECB-bonds will not be CDO-like in nature. Secondly, we do not expect European banks to be the main buyers but, rather, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and private investors. The key to the success of our Debt Conversion operation is the credibility of the ECB and, in a never-ending circle, the way that the latter is reinforced by credibility of the Debt Conversion plan itself. Thirdly, the Debt Conversion Plan’s credibility will be boosted, as argued above, by the superseniority status of the member-states’ debit accounts with the ECB.

To see what is at stake in a little more detail it helps to consider an example:

An example:

Consider the case of €100 million Spanish bonds owned by, say, Mr Nagiru of Yokohama. Purchase date: 2nd May 2005. Maturity date: 2nd May 2015

As things stand, on 2nd May 2015 Spain must borrow €100 million in order to repay Mr Nagiru by issuing a new bond. Consider its cost over a 20 year period while Spanish interest rates are around, say, r = 6%. In short, in 2015 Spain will have to issue 20 years bonds of a €302.56 million face value. In short, to roll over these €100 millions for the following 20 years (come 2nd May 2015) Spain will be committing itself to an interest payment of €202.56 million (payable on 2nd May 2035).

In contrast, under our Debt Conversion plan two interest rates will determine Spain’s cost of rolling over the same €100 millions. One is the interest rate that the ECB will manage to secure in the markets when selling its own ECB-bonds (call this recb) while a second interest rate, say rs, will apply to that funds Spain must raise on its own for the part of its debt that is over and above its Maastricht-Compliant level. To make our Debt Conversion work, recb<r and rs

≤r. [In fact, we are convinced that recb< rs << r. But more on this below.] Let us now compute Spain’s total interest savings over the 20 year period beginning on 2nd May 2015, in this example from our proposed Debt Conversion, under different interest rate assumptions:

Spain interest savings (s) from the Debt Conversion over the 2015-2035 period = Cost of refinancing without the ECB-brokered Debt Conversion (call it C) minus the cost of servicing the ECB’s own bonds (that involves paying E into the debit account opened by the ECB) minus the repayments R of the Spanish bonds that Spain must issue on 2nd May 2015 in order to roll over the part of the debt not serviced by the ECB (i.e. the part of the €100 million over and above its Maastricht quota). In short,

s = C-E-R =

where μ is the proportion of the country’s debt which is Maastricht Compliant – see Appendix.

The following table depicts the interest savings made possible by our Debt Conversion under different assumptions regarding interest rates recb and rs while supposing the interest rate Spain would have access to sans the ECB’s Debt Conversion will be around 6% (more or less as now). [Note that I am assuming that Spain’s μ will remain as today around 71% or 0.71.]

|

Reduction in interest due in 2035 from rolling over €100 million of Spanish debt in 2015 |

|||||

|

r |

6% (0.06) | 6% (0.06) | 6% (0.06) | 6% (0.06) | 6% (0.06) |

|

recb |

4% (0.04) | 3% (0.03) | 2.5%(0.025) | 3% (0.03) | 2% (0.02) |

|

rs |

6% (0.06) | 5% (0.05) | 3% (0.03) | 4% (0.04) | 4% (0.04) |

| Total interest saved (millions) | €65 | €104 | €138 | €116 | €138 |

| Interest saved as a % of interestpayable without the Debt Conversion | 21% | 34.4% | 43.61% | 38.33% | 43.61% |

It is clear from the above that Spain’s long term debt mountain can be massively reduced if the ECB manages to sell its bonds at interest rates below those that Spain can fetch presently. In the first column I present a conservative scenario: The ECB only achieves an interest rate that Germany would, today, consider unacceptably high (i.e. 4%), and nothing else changes. Still, Spain’s interest mountain will have shrunk by 21% over the twenty year period under consideration. As any market trader knows, this prospect is sufficient to spearhead an exit from the current vicious circle and the creation of a new virtuous circle.

More precisely, the moment the ECB-brokered Debt Conversion plan is announced, say tomorrow morning, the prospect of a considerable reduction in Spain’s aggregate interest payments will push Spain’s own interest rates lower. Suppose they diminish to, say, rs = 5%. Suddenly the markets will see that Spain’s outlook is improving and, therefore, will become less sceptical that it may fail to repay the due monies into its ECB debit account. As soon as this happens, recb will dip to, say, 3%. The second column now reports that the aggregate interest savings of Spain rises from 21% to an impressive 34.4%. This is enough to create even more optimism about both Spain and the ECB. If so, we are about to shift to one of the other scenaria (see for example the last column) in which Spain’s interest repayments shrink by more than 40% long run. Recalling that this is an operation that applies to all eurozone member-states (that opt for it) at once, imagine the scenes of jubilation in the global markets. As the eurozone’s interest mountain collapses, both recb and the rs of each country will be falling through the floor. The (so-called) debt crisis will then become history!

Naturally, the merits of any plan depend on the provisions made in case things go wrong. Plans, in other words, must come fully equipped with decent Plans B (unlike the eurozone’s original design). Investors are, therefore, likely to ask (as Koutras does): What if these best laid plans end up in ruins? What if this virtuous circle does not take off? To utilise our example above once more, if for some unforeseen reason Spain finds it hard to repay its debts to the last cent, and has to write down a portion of them, the fact that its ECB debit account obligations have superseniority status over its remaining debts means that the ECB will be unaffected. It will only be affected if Spain’s troubles in 2035 are beyond the pale (in the conservative scenario of the table’s first column it will have to effect a haircut more than 30%, in 2035, for the ECB to have to put its hand in its pocket to repay the ECB-bonds it issued on behalf of Spain). Even then, the common knowledge that either other member-states will come to Spain’s rescue (if it needs to write down more than 30% of its debts) or that the ECB will monetise (a small part of Spain’s debts to the ECB) is sufficient to keep investors safe in the thought that ECB bonds are an excellent investment even though no member-state stands behind them.

In summary, the beauty of our proposed Debt Conversion is that this inbuilt safety valve (the fact that the ECB will not need to fund its bonds from its own resources unless haircuts of more than 30% are necessary at nation-state level and other member-states do not come to the rescue) means that investors will flock to the ECB’s bond issues, spreads will fall throughout the eurozone (i.e. both recb and rs will be low) and, in a never-ending virtuous circle, member-states will have no need to haircut any part of their debt. With markets foreseeing this, investors will be queuing up around the block to subscribe to the ECB’s bond issues.

Is the ECB’s independence in peril? (Rejoinder IV, addressing point 4iii)

In an tumultuously interdependent world no constitution, treaty or charter can render anyone truly independent of the vagaries of human-induced disasters. Pretending otherwise is silly. Central Bank Independence, in this sense, must be clearly defined. When we say that some Central Bank is independent we do not mean that it can do as it pleases. What we mean is that the politicians cannot instruct it to print money on their behalf, to lower or to raise interest rates at their whim, to fund or not to fund some stricken bank depending on their judgment. The Modest Proposal poses no threat to this definition of the ECB’s independence. In fact, the Modest Proposal enhances the ECB’s current level of independence. For we must not forget that, as we speak, the ECB is forced by our politicians’ collective folly to print money (against its wishes) in order to buy Spanish and Italian bonds (against the express opinion of the Bundesbank) in the context of a war that it is bound to lose. The Debt Conversion proposed as part of Policy 1 of our Modest Proposal effectively liberates the ECB from this hopeless task imposed upon it by serially failing politicians.

Lastly, it is important to recall that the ECB’s charter assigns two tasks to the ECB’s executive board: To be the guardian of price stability and to serve the general policies of the Council. The latter creates a grey zone regarding the extent of the ECB’s infamous independence. We believe that the Modest Proposal, by furnishing the new instrument of ECB bonds, completes the ECB’s remit and gives it the tools it needs in order to do its job better and more (rather than less) independently.

Will member-states need to take any losses? (Rejoinder IV, addressing point 4iv)

Are they not taking losses now? Indeed they are. Kicking and screaming, countries that used to be considered part of the eurozone’s core are seeing their solvency questioned as good money is thrown after bad in a desperate bid to shore up the sinking EFSF-toxified ship. Our proposal will reverse this degenerative course, minimise member-state losses, and offer the currently missing hope of returning the eurozone project to solvency.

Are we mistaking an insolvency crisis for a liquidity problem (as the EU had been doing for two years now)? Are we introducing a moral hazard dimension capable of turning even the solvent into bankrupt states? (Rejoinder V, addressing point 4v above)

Confusing a solvency problem for a liquidity one was the mistake that the eurozone made with regard to its banks and, indeed, with Greece (and possibly Ireland, once Dublin had foolishly guaranteed the Irish banks’ bondholders). Koutras is right: It should not be repeated here. Thankfully, the Modest Proposal is doing no such thing. With regard to the banks, Policy 2 of the Modest Proposal broke new ground more than a year ago by suggesting that the banks are treated as quasi-insolvent and that the EFSF should become, effectively, a euro-TARP (an idea since then adopted by many, including US Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner). The question Koutras is asking is: Are we making this mistake with regard to the public finances of the member-states? If the ECB finances member-states ad infinitum what incentive do they have to put their fiscal house in order? Might the solvent ones not throw caution to the wind and opt for profligacy? My answer is: No, no, and no!

The key point here is that the ECB Debt Conversion operation concerns only the Maastricht Compliant debt. It splits a nation’s debt in two, making it easier to finance the ‘good’, or Maastricht Compliant, part of it but telling it, in no uncertain terms, that the rest must be serviced without assistance. In this sense, it creates a de facto penalty for profligacy which rewards member-states in proportion to their success in sticking to the Maastricht limit. At the same time, it gives member-states that are just above the Maastricht debt level (of 60% of GDP) every incentive needed to bring it below that level while introducing no incentive whatsoever for any member-state below that level to exceed it. Thus, the Modest Proposal, in effect, strengthens the Stability and Growth Path and removes (as opposed to reinforcing) moral hazard incentives.

In summary, the Modest Proposal manages, at once, (a) to help bring about debt relief for member-states (without haircuts or debt buy backs or fiscal transfers) and (b) to reduce moral hazard problems. I understand that it is hard to begin to wrap one’s mind around the possibility that combining (a) and (b) is possible. But it is. Keynes once, famously, exclaimed that the Treasury’s position at the time, with its constant invocation of moral hazard as an argument against debt relief, reminded him of the case of a drunkard who was dragged out of the icy waters he had fallen in due to his inebriation. The Treasury’s position, according to Keynes, was that the drunkard should not be wrapped in a blanket because (a) the cause of his troubles was the initial overheating of his brain (caused by alcohol consumption) and (b) he will ‘overheat’ again given a chance. If our task is to save the patient, it is important to overcome this attitude. The Debt Conversion plan (Policy 1) of the Modest Proposal intends to save the patient without, in itself, either adding new moral hazard problem or removing the original causes of the troubles. In this sense, it is a necessary though not sufficient operation (just like wrapping up the frozen drunkard in a dry blanket is a prerequisite to saving him, but no guarantee he will not get drunk again and end up in the icy waters once more).

What would make it sufficient? Policy 3 of the Modest Proposal tries to answer that question and goes to the heart of the solvency issue raised by Koutras (who, however, does not discuss Policy 3). Readers can read Policy 3 here themselves and pass judgment on it accordingly. The simple idea is to combine the European Investment Banks’ (EIB) own bond financing capacity with additional net issues of ECB bonds (in the context of EIB-ECB collaborative investment projects) in order, effectively, to create two processes: (1) A process that channels global (as well as European) savings into investment projects within Europe, and (2) another process which takes surpluses from the surplus countries of the eurozone and invests them in profitable small and medium enterprises in the deficit areas, thus undoing the intra-european imbalances which are the root cause of the eurozone’s structural problems.

Confusing monetary and fiscal policy in a manner that deepens the democratic deficit (Rejoinder VI, addressing points 4vi, 4vii & 4viii above)

This criticism is not new and I have responded to it many times in the past. Here is an extract from a post last May in which I wrote:

“Your proposal” we are told in no uncertain terms “asks of the ECB to perform not monetary, which is its remit, but fiscal policy! This is not allowed! It is beyond the pale!” But is it beyond the pale? Is it true that Policy 1 falls under the heading ‘fiscal policy’ and, thus, outside the realm that is the ECB’s natural habitat? We most certainly do not think so. Let us explain:

Collective debt management in our European currency union is a kind of interface, as much monetary as fiscal policy. It is fiscal policy only when debt is newly issued. However, once it is issued, the manner in which it is serviced can be another matter. To be blunt, debt management, is part and parcel of monetary, not fiscal, policy. According to Policy 1, the ECB will not be issuing member-country sovereign debt. It will be issuing its own supra-sovereign eurozone-debt, as and when it deems right in pursuit of its own monetary policy objective, the monetary counter-inflation targeting rule.[2]

To further underline the nature of this defining differentia specifica, the ECB does not (speaking strictly) need to issue its own new debt in order to service seasoned debt. It could just as well do this by creating new money (as the Fed has been doing). What Policy 1 is proposing is that, instead of quantitative easing US-style, the ECB borrows from the market for monetary policy purposes, recoup these monies long term from the eurozone’s member-states and make money in the process (therefore strengthening its own balance sheet). How much clearer can this be? And why is this inconsistent with the ECB’s remit?

[Click here for the whole post.]

Conclusion

The main criticism that the Modest Proposal has encountered is that the proposed ECB-bonds have no taxpayer behind them as a ‘backstop’ and, therefore, the only backstop imaginable is that the ECB must be prepared to print money to cover potential losses. This is wholly inaccurate. Our proposed ECB-bonds are part of a Debt Conversion plan on behalf of the member-states which do have their taxpayers behind them. In this sense, the ECB bonds also have (these same) taxpayers behind them.

So, what is the difference between ECB-bonds and a jointly and severally guaranteed eurobond to be issued by some European Debt Agency? ECB-bonds do not need German guarantees for the bonds that will be issued (by the ECB) on behalf of Spain or Italy or, indeed, every member-state that chooses to participate. It is in this sense that our Debt Conversion plan remain within the letter, but also the spirit, of the Lisbon Treaty while, at the same time, removing the currently inexorable pressure on the ECB to print, print and print.

Does this mean that the ECB, under our Debt Conversion plan, will never have to print under any imaginable circumstances? No, it does not. If in twenty years some eurozone member state needs to write down more than 20% or 30% of its sovereign debt, and the rest of the member-states (or the IMF) do not come to its assistance, it is then (and only then) possible to imagine that the ECB will have to print a very small amount in order to service the part of its own bonds that the said member-state could not service. (Certainly less than what they are printing now!) But then again, has there ever been any country in the world where there was a cast iron guarantee that its Central Bank will never have to monetise even a small part of its debt? What nonsensical mindset requires of us such a guarantee on behalf of a Central Bank? (Jan Toporowski answers this question brilliantly by referring us to the history of Nazi financing.) To argue that our Debt Conversion proposal is equivalent to having the ECB backstop the proposed ECB-bonds is no less disingenuous than suggesting that the Bundesbank was being asked by the Federal Republic to monetise Germany’s debt during the pre-euro era.

Next, I want to stress once again the importance of ECB bonds in dealing with the deeper causes of the Crisis, as opposed to simply offering a clever financial operation for dealing with the symptoms (i.e. with debt). As we have argued repeatedly, and Martin Wolf has recently reiterated in the FT, the eurozone’s real problem boils down to its internal trade (and productivity) imbalances; imbalances that can only be sorted out my means of targeted investment in the deficit regions and, therefore, surplus recycling. The great advantage of our ECB-bonds (which Koutras’ paper neglects to mention) is that the associated debit accounts that, according to our Modest Proposal each member-state will now have with the ECB, make it possible for a net issue of these ECB-bonds to be charged to the member-state’s account for investment projects carried out by the EIB in the member-state’s territory. It is this integration of Debt Conversion and a New Deal for Europe that makes the proposed ECB-bonds such powerful tools in the fight to the death against this current debilitating Crisis.

Finally, Koutras ends his paper with the suggestion that the weaknesses of the Modest Proposal he had identified are the reason why it “…has not captured the market practitioner’s imagination or the banker’s acceptance”. Let me say that this is certainly not my understanding. First, during the past few months I have presented the Modest Proposal to hedge funds, large banks, people at the fixed income department of Bloomberg (in New York), central bankers in the US and elsewhere etc. Almost to a person they seemed quite convinced about its merits. While it is true that many initially objected in a manner not dissimilar to Koutras’, upon hearing the above explanations their objections disappeared. Which, of course, leaves the question unanswered: Why has the Modest Proposal not been adopted? The reason is to be, I am convinced, found in the realm of politics and not public finance. To put it crudely (see here for an earlier take), because those with the political power to effect it fear that doing so will diminish their… political power. Such is the, almost ancient Greek, tragedy facing Europe today: Europe resembles a stage upon which its central characters are trapped in behavioural patterns that even the last member of the audience knows will take them straight to their Fall.

Lastly, my thanks to Andreas Koutras for his critical paper. It gave me an opportunity to revisit the Modest Proposal and re-state its raison d’ être.

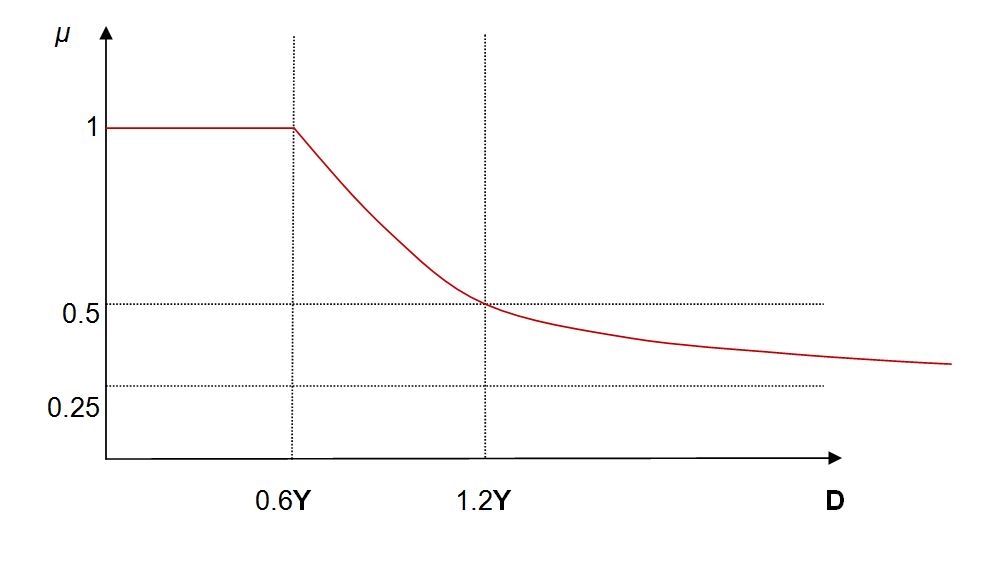

Appendix: The Maastricht Compliant Debt Proportion μ

Suppose that a member-state’s total public debt equals D. Then, if μ denotes the proportion of D that is Maastricht Compliant, then μ equals 1 as long as D ≤ 0.6Y (where Y is the nation’s GDP) or μ is given by the ratio 0.6Y/D if D exceeds the Maastricht limit of 0.6Y). Diagrammatically,

[1] Email address andreas@itcmarkets.com, website:

http://andreaskoutras.blogspot.com